Contributed by Edward Mitchell

Laboratory of Soil Biodiversity, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Vincent Jassey recently reported on tropical testate amoebae and especially those living in tank bromeliads (Jassey, 2017). These habitats are absent from higher latitude regions where winter frost would prevent the growth of such plants. Such “unusual” habitats are likely to house equally unusual testate amoebae and are therefore attractive for collecting samples to discover unknown microbial diversity.

More generally, tropical and higher latitude frost-free (e.g. hyper-oceanic) regions are likely to host a high diversity of testate amoebae. Recently several studies have explored these regions and confirm that indeed there is still a lot to learn regarding the diversity and ecology of testate amoebae.

For example, in a recent latitudinal study in Chile, Fernández et al. (2015, 2016) showed that testate amoeba diversity peaked at mid-latitude (ca. 40° S) corresponding to the Valdivian rain forest, a habitat characterised by high moisture and mild to warm temperatures (Fernández et al., 2015). This habitat is believed to correspond to the climatic conditions under which many lineages evolved, i.e. the need for high humidity and mild temperatures is a phylogenetically conserved trait (Fernández et al., 2016). Conditions further south are less favourable because the climate is harsher. conditions further north towards the tropics, despite being warm becomes increasingly dry up to the Atacama Desert, the driest place on Earth. Chile therefore is an ideal country to conduct research on latitudinal gradients of biodiversity.

However, even in apparently suboptimal conditions such as arid environments, interesting work can be done on testate amoebae. Leonardo Fernández explored the diversity patterns in a desert shrub-land and observed a nested pattern of diversity with communities in open, more exposed soil between bushes representing a sub-set of those living in the more favourable (or should we say less unfavourable) conditions (higher shading and thus likely more often or longer moist) beneath the bushes (Fernández, 2015).

These less studied regions also represent excellent opportunities to discover new testate amoeba species. Several recent examples are listed here:

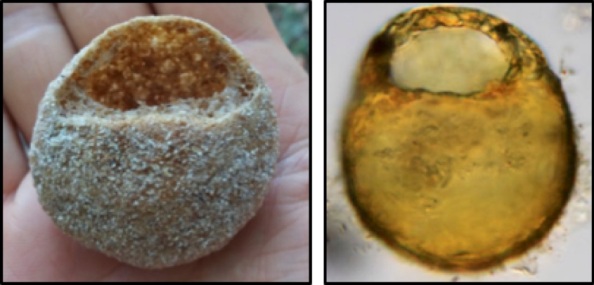

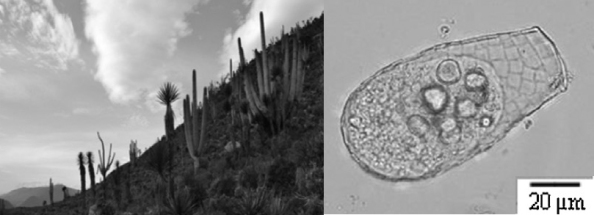

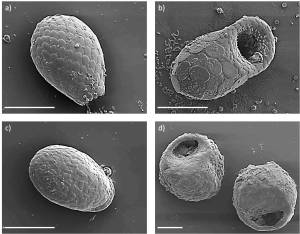

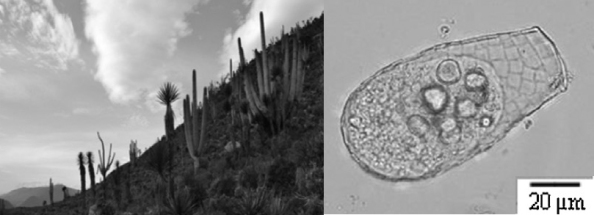

Recently Horacio Pérez-Juárez studied the testate amoeba communities from an arid environment in Mexico (Pérez-Juárez et al., 2017). Perhaps not surprisingly he discovered a new species. The surprise however was that new species Quadrulella texcalense (Fig. 1), belongs to a genus that is best known from wet habitats such as fens. This illustrates well that when we explore “unusual” habitats we may be in for some surprises!

Fig. 1. Vegetation of Cerro Marrubio (San Antonion Texcala, Puebla, Mexico) and one of the barcoded specimen of Quadrulella texcalense (modified from Pérez-Juárez et al., 2017).

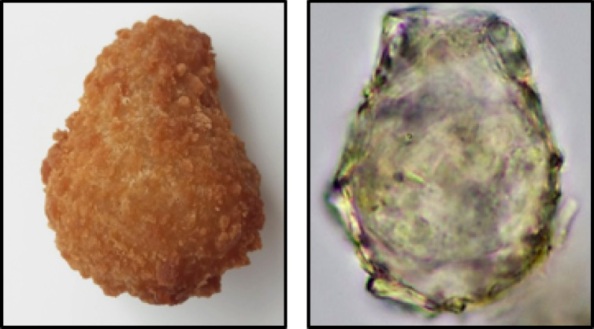

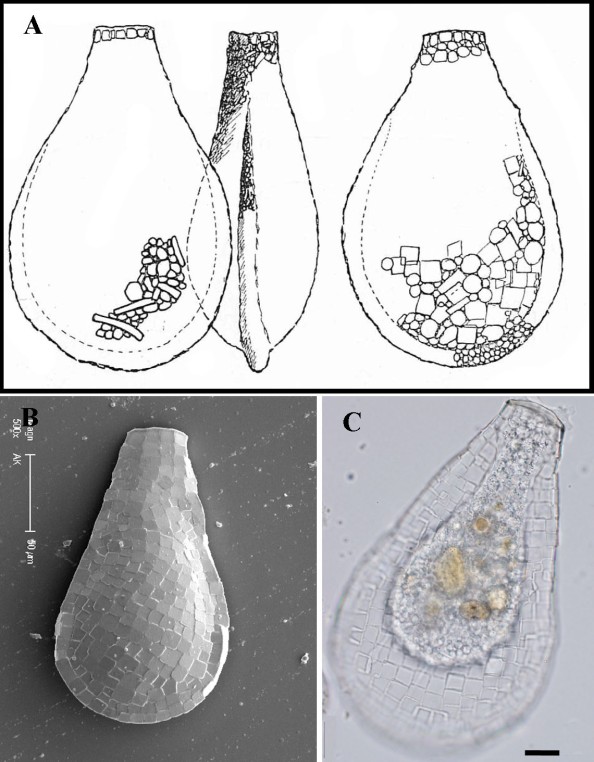

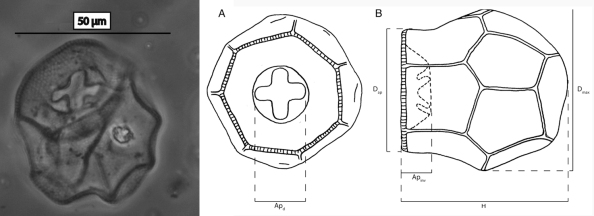

Graeme Swindles and colleagues have recently studied the diversity and ecology of testate amoebae in the Amazon and Central America. Again, not surprisingly they found a new species, Arcella peruviana (Fig. 2), described by Monika Reczuga (Reczuga et al., 2015). This relatively small, but unmistakable species has a highly unusual lobed aperture.

Fig. 2. Arcella peruviana from Reczuga et al. 2015. The diameter (D) is on average 47µm.

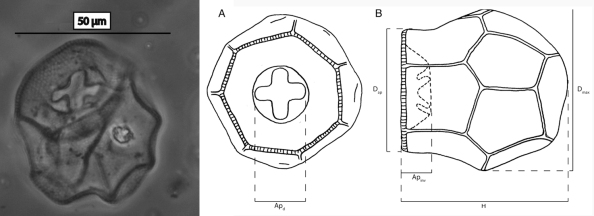

Another highly conspicuous species in genus Arcella was previously reported in this blog when discussing scientific names: Arcella gandalfi (Féres et al., 2016) (Fig. 3) (https://testateamoebaeresearch.wordpress.com/2017/02/17/whats-in-a-name-something-completely-different-to-be-said-about-taxonomic-nomenclature/). It is unclear if genus Arcella is especially diverse in the tropics. These amoebae are obviously easy to spot in a microscopic preparation (unlike smaller taxa such as Cryptodifflugia). To determine the possible existence of regional diversity hotspots and evolutionary radiation we clearly need more systematic inventories. With the growing interest in testate amoeba diversity, evolution and ecology we may hopefully be approaching a day when we will see a global inventory of testate amoebae take place!

Fig. 3. Arcella gandalfi, (modified from Féres et al., 2016). The test is on average 81µm in diameter (i.e. base of “Gandalf’s hat”).

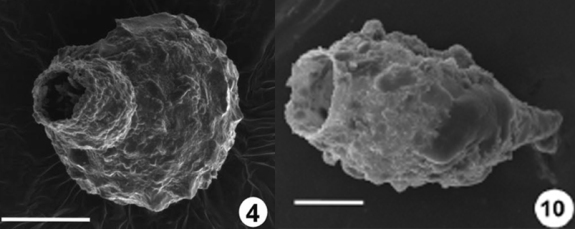

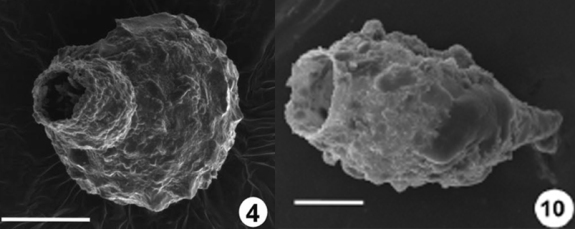

Two new Pontigulasia species were recently described from aquatic habitats China (Fig. 4). The fact that such large species had not been described before suggests that there are indeed still many new species to describe in China as in other under-studied regions of the World.

Pontigulasia pentagulostoma (left) and P. zhangduensis (right) (modified from Qin, Xie, Gu, et al., 2008 and Qin, Xie, et al., 2008b). Scale bars: 100µm (left) and 50µm (right).

Tropical and other less studied regions also represent good opportunities to study the ecology of testate amoebae, either specifically or in relation to other soil or water organisms, ecosystem functioning, human impact and other relevant questions. A few examples are listed here:

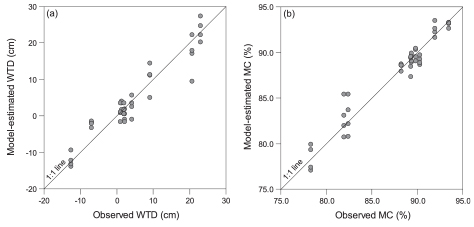

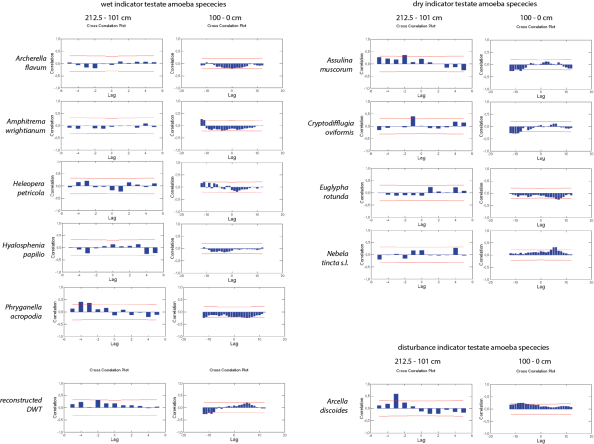

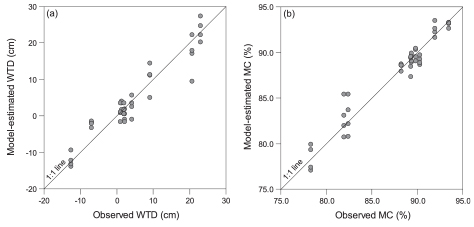

Graeme Swindles and colleagues built a transfer function from Peruvian Amazonia (Swindles et al., 2014). They then applied it to a palaeo-environmental study in Peruvian Amazonia (Swindles et al., 2016). Although peat preservation was not optimal a usable palaeo-environmental record could be obtained. Interestingly, the same transfer function was then also used in an ecological study of a coastal peatland in Panama (Swindles et al., 2018). The comparison of measured and transfer function-inferred water table depth and moisture content (Fig. 5) showed that the Peruvian transfer function performed very well indeed, thus showing that this approach holds much promises also in the tropics.

Fig. 5. Biplots of observed water table depth (WTD) and moisture content (MC) in coastal wetland of Panama vs. values predicted using a testate amoeba transfer function from Peruvian Amazonia (modified from Swindles et al., 2018).

In other tropical and subtropical regions, research on testate amoebae is also increasing, such as China (Qin et al., 2011, Li et al., 2010, Bobrov et al., 2015, Qin, Xie, Gu, et al., 2008, Qin, Xie, Swindles, et al., 2008, Qin et al., 2009, Qin et al., 2010, Qin and Xie, 2011, Qin et al., 2012, Qin, Fournier, et al., 2013, Qin, Mitchell, et al., 2013, Qin et al., 2016), Ecuador and Indonesia (Krashevska, 2008, Krashevska et al., 2008, Krashevska, Maraun, Ruess, et al., 2010, Krashevska, Maraun and Scheu, 2010, Krashevska, Maraun, et al., 2012, Krashevska, Sandmann, et al., 2012, Krashevska et al., 2014, Krashevska et al., 2015, Krashevska et al., 2016, Krashevska et al., 2017). These works (and others likely, this report does not aim to be exhaustive!) would deserve to be presented in this blog in more detail! We clearly can expect to learn much more about both diversity patterns and the ecology of testate amoebae beyond the more intensively studied temperate and boreal regions. This is very good news indeed!

Substantial work on testate amoebae has been done over the years in the tropics. But most of this literature is quite old and most of the scientists who conducted them are no longer active, the “Thecamoebian Bibliography” compiled by such scientists provides an very useful compilation of the literature (Medioli et al., 2003). It is therefore a very good signal to see younger researchers working again in these regions.

Working in the tropics can be challenging, and is most often more difficult than nearer the comfort of the higher latitude institutions where most active testate amoeba researchers work. Place or residence and possible logistical or administrative complications result in less research being conducted in the tropics. The payoff if however clearly there. Novel findings are very likely, many new species remain to be described and the community ecology of testate amoebae in different types of ecosystems may either confirm ideas derived from comparable studies in colder climate or else lead us to think differently. Extending our efforts to these regions will help balance the effort and may challenge some long-held opinions. And this of course is essential!

References

Bobrov, A., Qin, Y. & Wilkinson, D.M. (2015) Latitudinal Diversity Gradients in Free-living Microorganisms – Hoogenraadia a Key Genus in Testate Amoebae Biogeography. Acta Protozoologica, 54, 1-8.

Féres, J.C., Porfírio-Sousa, A.L., Ribeiro, G.M., Rocha, G.M., Sterza, J.M., Souza, M.B.G., Soares, C.E.A. & Lahr, D.J.G. (2016) Morphological and Morphometric Description of a Novel Shelled Amoeba Arcella gandalfi sp. nov. (Amoebozoa: Arcellinida) from Brazilian Continental Waters Acta Protozoologica, 55(4).

Fernández, L.D. (2015) Source-sink dynamics shapes the spatial distribution of soil protists in an arid shrubland of northern Chile. Journal of Arid Environments, 113, 121-125.

Fernández, L.D., Fournier, B., Rivera, R., Lara, E., Mitchell, E.A.D. & Hernández, C.E. (2016) Water–energy balance, past ecological perturbations and evolutionary constraints shape the latitudinal diversity gradient of soil testate amoebae in southwestern South America. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 25, 1216–1227.

Fernández, L.D., Lara, E. & Mitchell, E.A.D. (2015) Checklist, diversity and distribution of testate amoebae in Chile. European Journal of Protistology, 51, 409-424.

Jassey, V.E.J. (2017) Why living in the tropics is Awesome? From inside the shell – Blog of the International Society for Testate Amoeba Research (eds R. K. Booth, D. J. G. Lahr, E. A. D. Mitchell & J. E. J. Jassey).

Krashevska, V. (2008) Diversity and community structure of testate amoebae (Protista) in tropical montane rain forests of southern Ecuador: altitudinal gradient, aboveground habitats and nutrient limitation. Ph.D. Ph.D., Technischen Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt.

Krashevska, V., Bonkowski, M., Maraun, M., Ruess, L., Kandeler, E. & Scheu, S. (2008) Microorganisms as driving factors for the community structure of testate amoebae along an altitudinal transect in tropical mountain rain forests Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 40, 2427–2433.

Krashevska, V., Klarner, B., Widyastuti, R., Maraun, M. & Scheu, S. (2015) Impact of tropical lowland rainforest conversion into rubber and oil palm plantations on soil microbial communities. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 51, 697-705.

Krashevska, V., Klarner, B., Widyastuti, R., Maraun, M. & Scheu, S. (2016) Changes in Structure and Functioning of Protist (Testate Amoebae) Communities Due to Conversion of Lowland Rainforest into Rubber and Oil Palm Plantations. PLoS ONE, 11, e0160179.

Krashevska, V., Maraun, M., Ruess, L. & Scheu, S. (2010) Carbon and nutrient limitation of soil microorganisms and microbial grazers in a tropical montane rain forest. Oikos, 119, 1020-1028.

Krashevska, V., Maraun, M. & Scheu, S. (2010) Micro- and Macroscale Changes in Density and Diversity of Testate Amoebae of Tropical Montane Rain Forests of Southern Ecuador. Acta Protozoologica, 49, 17-28.

Krashevska, V., Maraun, M. & Scheu, S. (2012) How does litter quality affect the community of soil protists (testate amoebae) of tropical montane rainforests? FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 80, 603-607.

Krashevska, V., Sandmann, D., Maraun, M. & Scheu, S. (2012) Consequences of exclusion of precipitation on microorganisms and microbial consumers in montane tropical rainforests. Oecologia, 170, 1067-1076.

Krashevska, V., Sandmann, D., Maraun, M. & Scheu, S. (2014) Moderate changes in nutrient input alter tropical microbial and protist communities and belowground linkages. ISME Journal, 8, 1126–1134

Krashevska, V., Sandmann, D., Marian, F., Maraun, M. & Scheu, S. (2017) Leaf Litter Chemistry Drives the Structure and Composition of Soil Testate Amoeba Communities in a Tropical Montane Rainforest of the Ecuadorian Andes. Microbial Ecology, 74, 681-690.

Li, H.K., Wang, S.Z., Bu, Z.J., Zhao, H.Y., An, Z.S., Mitchell, E.A.D. & Ma, Y.Y. (2010) The testate amoebae in Sphagnum peatlands in Changbai Mountains. Wetland Science, 8, 249-255.

Medioli, F.S., Bonnet, L., Scott, D.B. & Medioli, B.E. (2003) The Thecamoebian Bibliography, 2nd edition. Palaeontologia Electronica, 6, 107.

Pérez-Juárez, H., Serrano-Vázquez, A., Kosakyan, A., Mitchell, E.A.D., Rivera Aguilar, V.M., Lahr, D.J.G., Hernández Moreno, M.M., Cuellar, H.M., Eguiarte, L.E. & Lara, E. (2017) Quadrulella texcalense sp. nov. from a Mexican desert: An unexpected new environment for hyalospheniid testate amoebae. European Journal of Protistology, 61, 253-264.

Qin, Y., Booth, R.K., Gu, Y., Wang, Y. & Xie, S. (2009) Testate amoebae as indicators of 20th century environmental change in Lake Zhangdu, China Fundamental and Applied Limnology, 175, 29-38.

Qin, Y., Fournier, B., Lara, E., Gu, Y., Wang, H., Cui, Y., Zhang, X. & Mitchell, E.A.D. (2013) Relationships between testate amoeba communities and water quality in Lake Donghu, a large alkaline lake in Wuhan, China. Frontiers of Earth Science, 7, 182-190.

Qin, Y., Mitchell, E.A.D., Lamentowicz, M., Payne, R.J., Lara, E., Gu, Y., Huang, X. & Wang, H. (2013) Ecology of testate amoebae in peatlands of central China and development of a transfer function for paleohydrological reconstruction. Journal of Paleolimnology, 50, 319-330.

Qin, Y., Payne, R.J., Gu, Y., Huang, X. & Wang, H. (2012) Ecology of testate amoebae in Dajiuhu peatland of Shennongjia Mountains, China, in relation to hydrology. Frontiers of Earth Science, 6, 57-65.

Qin, Y., Wang, J., Xie, S., Huang, X., Yang, H., Tan, K. & Zhang, Z. (2010) Morphological Variation and Habitat Selection of Testate Amoebae in Dajiuhu Peatland, Central China. Journal of Earth Science, 21, 253-256.

Qin, Y. & Xie, S. (2011) Moss-dwelling testate amoebae and their community in Dajiuhu peatland of Shennongjia Mountains, China. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 26, 3-9.

Qin, Y., Xie, S., Gu, Y. & Zhou, X. (2008) Pontigulasia pentangulostoma nov spec., a New Testate Amoeba from the Da Jiuhu Peatland of the Shennongjia Mountains, China. Acta Protozoologica, 47, 155-160.

Qin, Y., Xie, S., Smith, H.G., Swindles, G.T. & Gu, Y. (2011) Diversity, distribution and biogeography of testate amoebae in China: Implications for ecological studies in Asia. European Journal of Protistology, 47, 1-9.

Qin, Y., Xie, S., Swindles, G.T., Gu, Y. & Zhou, X. (2008) Pentagonia zhangduensis nov spec. (Lobosea, Arcellinida), a new freshwater species from China. European Journal of Protistology, 44, 287-290.

Qin, Y.M., Man, B.Y., Kosakyan, A., Lara, E., Gu, Y.S., Wang, H.M. & Mitchell, E.A.D. (2016) Nebela jiuhuensis nov sp (Amoebozoa; Arcellinida; Hyalospheniidae): A New Member of the Nebela saccifera – equicalceus – ansata Group Described from Sphagnum Peatlands in South-Central China. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 63, 558-566.

Reczuga, M.K., Swindles, G.T., Grewling, L. & Lamentowicz, M. (2015) Arcella peruviana sp nov (Amoebozoa: Arcellinida, Arcellidae), a new species from a tropical peatland in Amazonia. European Journal of Protistology, 51, 437-449.

Swindles, G.T., Baird, A.J., Kilbride, E., Low, R. & Lopez, O. (2018) Testing the relationship between testate amoeba community composition and environmental variables in a coastal tropical peatland. Ecological Indicators, 91, 636-644.

Swindles, G.T., Lamentowicz, M., Reczuga, M. & Galloway, J.M. (2016) Palaeoecology of testate amoebae in a tropical peatland. European Journal of Protistology, 55, 181-189.

Swindles, G.T., Reczuga, M., Lamentowicz, M., Raby, C.L., Turner, T.E., Charman, D.J., Gallego-Sala, A., Valderrama, E., Williams, C., Draper, F., Coronado, E.N.H., Roucoux, K.H., Baker, T. & Mullan, D.J. (2014) Ecology of Testate Amoebae in an Amazonian Peatland and Development of a Transfer Function for Palaeohydrological Reconstruction. Microbial Ecology, 68, 284-298.